A Family History

Click here to view Artist’s Statement

Click here to view essay: From the memoirs of Alexander Herzen

Click here to view essay: From Dr. Zhivago by Boris Pasternak

My Uncle Maurice was an educated man who came from Panama to find a Jewish woman to marry & married Ruth (on the left). He spoke many languages including German & was dropped behind enemy lines by the Army. After the war he started an import-export business concentrating on South America that seemed to do exceedingly well no matter what the economy. When he died, we found out that he had become a CIA agent & the business was partially a cover…

After the war, my Aunt Dotty (2nd from left) married Harry who us kids considered stark raving mad. (He’s described precisely in Bob Dylan’s I Pity the Poor Immigrant.) It was explained to me thus: “Harry & his brother were trapped by the German invasion of Poland. They fled east, just ahead of the German lines for many months, living on grass or whatever, until they finally reached the Russian lines. Made him crazy.”

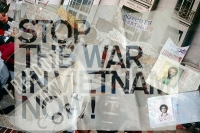

Artist’s Statement

All images are multiple exposures made in the camera. Some, in addition, contain painting.

From My Past & Thoughts, the memoirs of Alexander Herzen

(Traveling across Russia in the 1830’s, he reaches “a very poor Votyak village”.)

….A soldier came in & reported that an escorting officer had sent to invite me to a cup of tea. “With the greatest pleasure”. I followed him.

A short, elderly officer with a face that bore traces of many anxieties, petty necessities & fear of his superiors met me.

“Whom are you taking, & where to?”

“Don’t ask; it’d break your heart. Well, I suppose my superiors know all about it; It’s our duty to carry out orders & we are not responsible but it’s an ugly business.

They have collected a crowd of cursed little Jew boys of eight or nine years old. Whether they are taking them for the navy or what I can’t say. At first the orders were to drive them to Perm; then there was a change & we are driving them to Kazan. I took them over a hundred versts farther back. The officer who handed them over said “It’s dreadful, & that’s all about it; a third were left on the way.” (& the officer pointed to the earth). “Not half who remain will reach their destination.”

“Have there been epidemics, or what?” I asked, deeply moved.

“No, not epidemics, but they just die off like flies. A Jew boy, you know, is such a frail, weakly creature, like a skinned cat; he is not used to tramping in the mud for ten hours a day & eating biscuit – then again, being among strangers, no father nor mother nor petting; well, they cough & cough until they cough themselves into their graves. And I ask you, what use is it to them? What can they do with little boys?”

I made no answer. “When do you set off?” I asked.

“Well, we ought to have gone long ago, but it has been raining so heavily

….Hey, you there, soldier! Tell them to get the small fry together.”

They brought the children & formed them into regular ranks; it was one of the most awful sights I have ever seen, those poor children! Boys of twelve or thirteen might somehow have survived it, but little fellows of eight & ten…Not even a brush full of black paint could put such horror on canvas.

Pale, exhausted, with frightened faces, they stood in thick, clumsy, soldier’s overcoats, with stand up collars, fixing helpless, pitiful eyes on the garrison soldiers who were roughly getting them into ranks. The white lips, the blue rings under their eyes bore witness to fever or chill. And these sick children, without care or kindness, exposed to the icy wind that blows unobstructed from the Arctic Ocean, were going to their graves.

From Dr. Zhivago by Boris Pasternak

(It is the first world war. Yuri Andreevich Zhivago, being a physician, is an officer in the Russian army.)

In this sector the villages had been preserved in some miraculous way. They made up an inexplicably intact island in the midst of destruction. Gordon & Zhivago were returning home in the evening. The sun was setting. In one of the villages they rode past, a young Cossack, to the unanimous guffawing of those around him, was making an old gray-bearded Jew in a long overcoat catch a five-kopeck copper coin he tossed in the air. The old man invariably failed to catch it. The coin, falling through his pathetically spread hands, fell in the mud. The old man bent down to pick it up, the Cossack slapped his behind, those standing around held their sides & moaned with laughter. This constituted the whole amusement. So far it was inoffensive, but no one could guarantee that it would not take a more serious turn. His old woman would come running from a cottage across the road, shouting & reaching her arms out to him, & each time would disappear again in fright. Two little girls looked at their grandfather through the window & wept.

The driver, who found it all killingly funny, slowed the horses’ pace to give the gentlemen time to amuse themselves. But Zhivago, calling the Cossack over, reprimanded him & told him to stop the mockery.

“Yes sir,” the man said readily. “We didn’t mean nothing, it was just for laughs.”

For the rest of the way Zhivago & Gordon were silent.

“It’s terrible,” Yuri Andreevich began, when their own village came in sight. “You can hardly imagine what a cup of suffering the unfortunate Jewish populace has drunk during this war. It’s being conducted right within the pale of their forced settlement. And for all they’ve endured, for the sufferings, the taunts, & the accusation that these people lack patriotism. But where are they to get it, when they enjoy all rights with the enemy, & with us they’re only subjected to persecution? The very hatred of them, the basis of it, is contradictory. What vexes people is just what should touch them & win them over. Their poverty & overcrowding, their weakness & inability to fend off blows. Incomprehensible. There’s something fateful in it.”

Gordon made no reply.

From Admiral of the Ocean Sea by Samuel Eliot Morrison, a biography of Columbus, published in 1942.

Columbus did not once mention in his writings a tragic movement that was under way at the same time as his preparations, one which must in some measure have hampered his efforts & delayed his departure. This was the expulsion of the jews from Spain. On March 30, 1492, one month before concluding their agreements with Columbus, Ferdinand & Isabella signed the fateful decree giving the jews four months to accept baptism or leave a country where many thousands of them had made their home for centuries, & to whose intellectual life they had contributed in a degree far beyond their numbers. As Columbus journeyed from Granada to Palos he must have been witness to heart-rending scenes similar to those which modern fanaticism has revived in the Europe of today. Swarms of refugees, who had sold for a trifle property accumulated over years of toil, crowded the roads that led seaward, on foot & leading donkeys & carts piled high with such household goods as could be transported. Rabbis read the sacred scrolls & others played the traditional chants on pipe & tabor to keep their spirits up; but it was a melancholy procession at best, what with weeping & lamenting, and the old & sick crawling into the fields to die. When they arrived at Puerto Santa Maria & for the first time beheld the ocean, the Jews raised loud cries & invocations, hoping that Jehovah would part the waters & lead them dry-shod to some new promised land. Camping where they could find room or crowded aboard vessels that the richer jews chartered, they forlornly awaited the order to leave; finally word came from the Sovereigns that every Jew-bearing ship must leave port on August 2, 1492, the day before Columbus set sail from Palos. Perhaps that is why he waited until the following day; but even then he did not avoid sailing in unwanted company. Sixty years later an old man deposed in Guatemala that he had been gromet on a ship of the great migration that dropped down the Rio Saltes on the same tide with the Columbian fleet; & by a curious coincidence, when his ship was sailing back to Northern Spain after discharging her cargo of human misery in the Levant, she met the Pinta returning from the great discovery, & heard news that in due time would give fresh life to this persecuted race.